On the coach from Arles I wriggle with glee to look out upon the Camargue delta. Pink flamingos, wild horses, bulls tended by those horse-backed cowboys, the gardians. Every spring I wing it down here to luxuriate in the sensuousness of southern France and, in particular, to the little seaside town of Saintes-Marie-de-la-Mer where, this time each year, the Romani of Europe gather for a week-long festival to honour their saint, Sara-la-Kali, the Black Madonna. The streets, as I wander out of my apartment, are full of revellers. It was here Gaugin and Van Gogh came to paint and in this golden dusk it is no wonder they went mad with colour. I sit at the back of the bar where the four-piece flamenco band is starting up. I sip camargues, the local liquor, and my soul sings to think of the great Gypsy musicians who have graced this town with their presence. Manitas de Plata, the little hands of silver, that veritable Don Juan, prince among men. Django Reinhardt, who composed his own black mass for the festival. Even that restless troubadour, Bob Dylan.

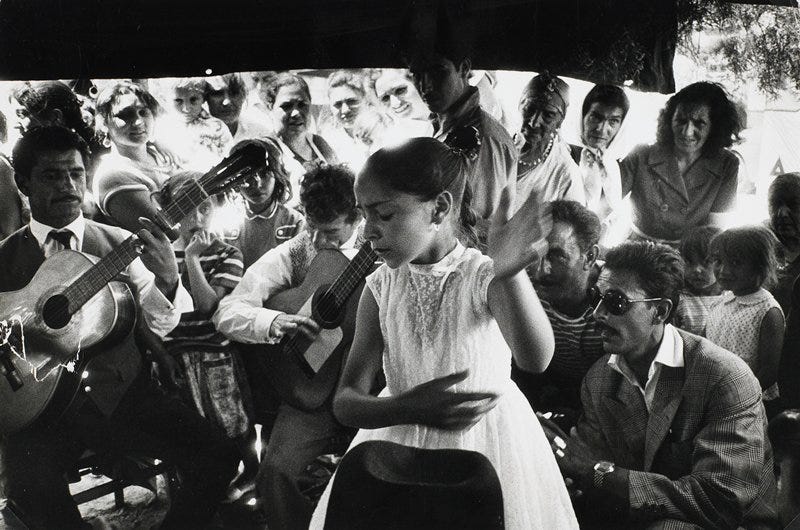

How I adore flamenco. This art form, invention of the Romani of Andalucía is, as Federico Garcia Lorca writes, almost synonymous with duende, those “dark sounds” which are “the very substance of art”. There is “neither map nor discipline” for seeking duende, the “most ancient culture of immediate creation”. Every artist knows access to true emotion is impossible without it. Neither angel nor muse it is a chthonic spirit that rises up from the earth and takes possession. In the late hours, I sit with others in the magic circle in the plaza by the church, listening to the Romani men take it in turns to sing and, occasionally, to dance. Each sings whenever he feels the urge, the spectators keep the beat, a solitary guitarist provides accompaniment. They strive for that depth of emotion that is the arrival of duende. The singing is slow, melismatic, full of melancholy, longing, anguish. ¡Olé!

I am transported back to the very origins of music. Herodotus tells us it was Linus, brother of Orpheus – a personification of the lament – who was the father of lyric song. The kommos, a lyrical song of lament, comes at the climax of Greek tragedy. Moreover, some scholars believe singing itself emerged from the lamentations of women mourners during funeral rites. The women weep, tear at their hair, as if possessed. They will not be consoled. And in their wavering cries, the uncanny movements of their arms, we find the first stirrings of music and ritual. Song was, in other words, from the beginning, a confrontation with the senselessness of death. It is perhaps no surprise, then, that duende is so conspicuous in Spain, the most thanatic country on earth. Duende, which, as Lorca tells us “won’t appear if he can’t see the possibility of death” is an underworld spirit and thus – like the underworld goddess Persephone – also associated with the sensuous mysteries of new life. Weeping is cathartic. It summons the spirits of the dead, gives birth to the new. Duende and, by extension, the origins of music, then, could be more readily associated with women than men, who are more sensuous in temperament and therefore more connected with earthly mysteries, and there is no greater earthly mystery than death.

No wonder, then, the lamentations of women were, from the beginnings of the city-state deemed an intolerable threat to social order, a dangerous contagion. The Athenian statesman Solon, according to Plutarch, banned them from the city’s funeral processions and festivals. Is men’s hatred of women not really a fearful hatred of their sensuous earthly origins, of the body and thus of life itself? Truer than ever today. Mammon, the rational-utilitarian demon that rules the modern world, is a phallic god. He desires, above all, slavish worship of order, abstraction, technology. Everything that is sensuous, feminine and unknowable he abhors, and in his obsessive desire to defeat death he is obliged to defeat life. But the spirit of duende shall never perish from the earth. And wherever the dispossessed, the wounded cry in anguish we are yet reminded of the strange, sensuous origins of the world.

I descend – the next day – into the crypt of the town’s church of Notre Dame-de-la-Mer where, beside a pagan altar once splattered with the gore of bulls sacrificed to Mithras, stands the slender ebony statue of Sara-La-Kali, Saint Sarah, the Black Madonna, coated in many layers of garments. The air is hot from thousands of candles that flicker over her face. The pilgrims fuss with her folds, whisper their prayers, kiss her forehead. I come face-to-face with her and it gives me a sensuous mystery-feeling. They say she was the Egyptian maidservant of the Three Marys, myrrh-bearing witnesses to Christ’s tomb, who arrived upon these shores in the 1st century. They built an oratory dedicated to the saviour and, in the 15th century, their bones were discovered beneath the foundations of the medieval structure and placed in reliquaries that still hang suspended above the church’s altar. The saints were honoured with Catholic feast days and the Christian ritual of immersing their statues in the sea once a year supplanted the local pagan cult. Somehow, worship of Sara-la-Kali became syncretised with the Christian festival and for the past century or more her Romani devotees also immerse her at this time of year. Her origins, like those of the Romani themselves, are actually in northern India. Sara is the namesake of Hindu goddess Kali whose likenesses her Indian devotees also ritually immerse in water. Kali resembles those ancient European goddesses – Ceres, Artemis, Isis – who preside over the mysteries of death and new life and as I rise again from the womb-like crypt I cannot help but think Sarah is an incarnation of the spirit of duende itself.

I indulge myself in a long, leisurely lunch. Crisp white wine that tastes of the sea. Two-dozen oysters. Then wander, glassy-eyed, through the festival. I hobnob with pilgrims. I sit beneath the junipers and listen to the flamenco players. Ah, the festival! There is nothing more leisurely in the world. A cessation of work. A chance to observe the beauty of the universe. And to do so in the company of others, to dissolve into the multitude! How we have neglected festivity, just as we have neglected leisureliness! Sure, we have our summer music festivals. But have these not also been corrupted by Mammon? One cannot move through a festival these days without crashing into an advertising hoarding or being accosted by that demonic emissary, the “corporate sponsor”. A true festival is sacred earth. A portion of land, like a temple, separated from the utilitarian world of need, accumulation and profit, and thus consecrated, made holy. But when we neglect the spirit of true festivity, that vital need to commune with the gods (“there is no true festival without the gods”!) pleasure becomes our only value and hedonism in the end only another tedious form of work. No, friends. It is only with true festivity that we can, like Nietzsche, “say yea to a single moment, then in so doing we have said yea not only to ourselves, but to all existence”.

The ancient philosophers – in their infinite wisdom – knew this. For Pythagoras, life itself was like a religious festival and the philosopher one who contemplates the spectacles, the parades, the rituals. In Plato’s Republic, Socrates declares that, in the ideal state, no fewer than three-hundred and sixty five festivals would be celebrated a year. Human beings, for Plato, are “playthings of the gods” and there is no better way to delight them than “sacrificing, dancing, and singing”. In other words, in the spirit of festivity. Moreover, the Greek word theoria – from which we derive theory – originally meant not only observation and contemplation, but a delegation on pilgrimage to a festival. You see philosophy itself was, for the ancients, a sacred journey and the destination – wisdom – first divined from the distant cry and clamour of the festival procession. Without festivity, wisdom itself becomes lost. And what was it that Yahweh demanded of the Israelites, before he led them out of slavery in Egypt, other than a festival in his honour in the desert? Festivity precedes liberation, a time in which the world appears to us in all its beauty, thus a time when we are freed from Mammon’s prison. It points, in other words, toward the final redemption of the world.

I muse, like this, as I wander bar to bar and toast glasses of camargues with my Romani comrades. And how deeply profound my thoughts become! Then, in the early afternoon, I gather with the other revellers in the plaza, hear the congregation inside the church chant “Vive Saint Sarah!” and, suddenly, through the doors I glimpse her rise from the crypt upon her litter like a queen. She turns her dark face toward us and I am swept in the bacchic maelstrom down to the beach, where, flanked by the horse-backed gardians, the statue is immersed in water and then resurfaces and it is at once, like life itself, so wondrously strange, beautiful and bathetic. I follow the singing pilgrims back up the streets and together we cry “¡Olé! ¡Olé! ¡Olé!”.

Nathaniel Edgars is a writer who lives in Malaga with his cat, Heidegger. His forthcoming book, The Lost Art of Leisure: A Personal View, will be published in 2026 by Skol Press.